By Amy Lv, Divya Rajagopal and Ernest Scheyder

BEIJING/TORONTO/LONDON (Reuters) – China’s trade restrictions on strategic minerals are starting to hit Western companies where it hurts.

Blaming the antimony exports announced in August on Beijing’s restrictions on antimony exports, Henkel, the German chemicals and consumer goods heavyweight, told customers last month that it had declared force majeure and suspended deliveries of four types of adhesives and lubricants commonly used by automakers, according to a Nov. 8 letter to customers reviewed by Reuters.

Henkel uses the silvery metal to make its Bonderite and Teroson brand products, core parts of the company’s adhesive technologies division, which generated 10.79 billion euros ($11.4 billion) in revenue last year.

“We have been informed by our suppliers that imports of these raw materials have been postponed pending the acceptance of license applications by the Chinese government,” said the letter, which was signed by two senior executives.

“As a result, Henkel hereby declares force majeure in connection with the deliveries of these products,” the German company also said, adding that it could not predict the duration of the situation.

Henkel’s previously unreported letter and conversations with more than two dozen traders, miners, processors, end users and industry experts in North America, Europe and China underscore and highlight the serious disruption caused by Beijing’s trade restrictions how Western players are struggling to replace China-based supply chains.

Contacted Reuters about the letter, Henkel said it was working to support its customers and find alternative supplies: “We are closely monitoring the global supply situation of antimony and are committed to finding solutions to meet our customers’ orders.” customers to meet.”

The price of antimony, scarce in nature but essential for military equipment such as ammunition, infrared missiles, nuclear weapons and night vision goggles, rose almost 230% this year to around $39,000 per tonne on the busy Rotterdam spot market, market information shows. supplier Argus.

China is the world’s largest antimony producer and dominates the production of many strategic materials.

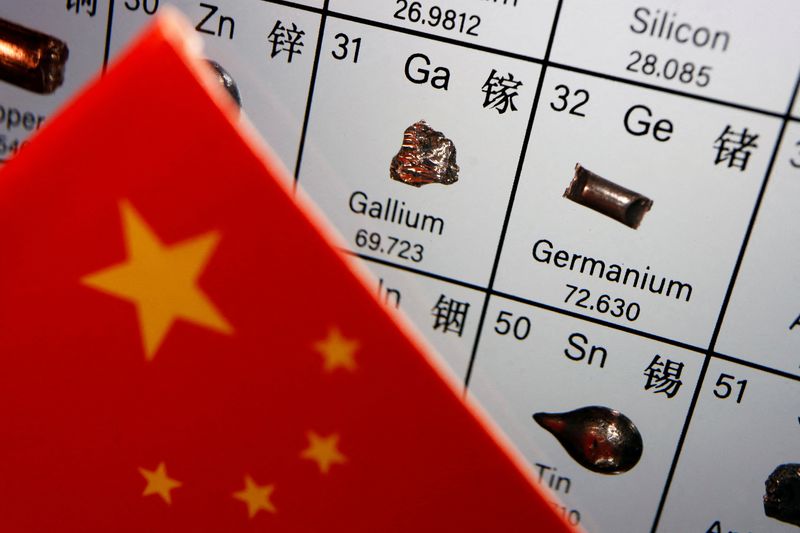

Last year, Beijing also restricted exports of gallium and germanium – used for semiconductors, solar panels and weapons – as well as certain types of graphite – a key component of EV batteries.

In response to a new US crackdown on China’s chip industry, Beijing increased pressure this week and imposed an outright ban on exports of gallium, germanium and antimony to the United States, where Henkel makes Bonderite in Michigan.

LOOKING FOR ALTERNATIVES

Beijing’s restrictions make it especially urgent for Western players to reduce their dependence on minerals from China.

For example, miner Perpetua Resources is developing an antimony mine in Idaho with funding from the U.S. government.

But it can take years for new mines to develop, forcing players like Henkel to look for alternatives, which are often more expensive.

“Please note that we are in close contact with our suppliers and are using all commercially reasonable means to leverage our global supply chain to address this situation and support our customers,” Henkel also wrote in the letter.

Meanwhile, some Western miners and processors have started building capacity.

United States Antimony (USAC), the sole North American processor of the metal, made plans to boost production at its Montana smelter, which was operating at 50% capacity, after China announced restrictions on antimony exports in August .

“Our decision to ramp up production was primarily driven by the more than tripling of global Rotterdam antimony prices,” company chairman Gary Evans told Reuters.

China’s restrictions “created significantly more demand for our end products,” he added.

at the Montana site was discontinued in 1983, when it was cheaper to source antimony from mines outside the United States, and environmental restrictions now prevent extraction there, the company said.

USAC, which is not dependent on China, is in talks to receive the material from four other countries and one domestic supplier as early as December, Evans said, declining to name them for competitive reasons.

Orders at Ottawa-based Northern Graphite, which bills itself as the only producer of natural graphite in North America, rose 50% in the wake of China’s graphite restrictions announced in October 2023, CEO Hugues Jacquemin told Reuters.

“When export controls came into effect in December last year, there was a significant increase in demand. We started ramping up capacity,” said Jacquemin, whose company is developing projects in Namibia and Ontario to build the Lac des Iles mine to expand. Quebec.

China accounts for more than 70% of the supply of both naturally extracted graphite and its synthetic variant.

Mark Jensen, CEO of ReElement Technologies, a branch of American sources (NASDAQ:), which specializes in recycling and refining rare earth metals, said China’s latest export ban means the company has received at least 10 calls this week from US miners offering zinc ore, which could be a source of germanium during the processing.

Those shipments had previously gone to China for processing because of lower labor costs and other environmental standards, he said.

“We have reached out to U.S. suppliers of these raw materials to sell these byproducts to us instead of sending them to China because we are now an alternative to China,” Jensen told Reuters.

Canadian miner Teck Resources (NYSE:), which produces germanium as a byproduct at its Red Dog zinc mine in Alaska and is the sole supplier of the metal in North America, told Reuters it is investigating whether to halt production of the critical material there can be increased. that China has blocked exports to the United States.

DISTURBED MARKETS

The Chinese export crisis has led to a rise in the prices of many strategic minerals.

Gallium sold outside China was 30% to 40% more expensive than in the People’s Republic in the first half of 2024 compared to a year earlier, according to Toronto-based Neo Performance Materials, which produces gallium by recycling manufacturing scrap, said in August .

In China, the restrictions have driven some weaker players out of the market, traders and analysts told Reuters.

Two Chinese germanium traders told Reuters they had given up exports because they could not secure licenses, either because foreign customers were unwilling to provide specific details about end users or because they were from the United States.

Even before Beijing’s latest restrictions hit the United States, no Chinese germanium or gallium was shipped there this year through October, Chinese customs data show. During the same period in 2023, the US was the fourth and fifth largest mineral export markets.

For end users, China’s restrictions underline the importance of diversifying supply.

“If you reduce risk, you have to reduce risk with different levers,” said Maxime Picat, chief purchasing officer at automaker Stellantis (NYSE:). “If you are a one-solution company, knowing that your battery suppliers are all Chinese or all Korean, you are at risk.”

($1 = 0.9465 euros)