By Rachel Savage and Duncan Miriri

JOHANNESBURG/NAIROBI (Reuters) – China’s flagship economic cooperation program is rebounding after a hiatus during the global pandemic, with Africa at the center, a Reuters analysis of credit, investment and trade data shows.

Chinese leaders have cited the billions of dollars invested in new construction projects and two-way trade as evidence of their commitment to helping modernize the continent and promoting “win-win” cooperation.

But the data shows a more complex relationship, one that is still largely extractive and has so far fallen short of Beijing’s rhetoric on the Belt and Road Initiative, President Xi Jinping’s strategy to build an infrastructure network that will connects with the world.

While new Chinese investment in Africa rose by 114% last year, according to the Griffith Asia Institute at Australia’s Griffith University, it was heavily focused on minerals essential to the global energy transition and on China’s plans to revive its own weak economy to blow in.

Those minerals and oil also dominated trade. As efforts to boost other imports from Africa, including agricultural and industrial goods, fail, the continent’s trade deficit with China has ballooned.

Chinese government borrowing, once the main source of financing for Africa’s infrastructure, is at its lowest level in two decades. And public-private partnerships (PPPs), which China has touted as its new investment vehicle of choice globally, have yet to gain traction in Africa.

The result is a more one-sided relationship than China says it wants, one dominated by imports of African raw materials and which some analysts say has echoes of Europe’s colonial-era economic ties with the continent.

“This is something that Britain would recognize in the late 19th century,” says Eric Olander, co-founder of the China-Global South Project website and podcast.

China rejects such claims.

“Africa has the right, capacity and wisdom to develop its external relations and choose its partners,” China’s Foreign Ministry wrote in response to Reuters’ questions.

“China’s practical support for Africa’s modernization path, in line with its own characteristics, has been welcomed by an increasing number of African countries.”

A PIVOT WITH POTENTIAL?

Chinese involvement in Africa, a focus of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), grew rapidly in the two decades before the COVID-19 pandemic. Chinese companies built ports, hydroelectric dams and railways across the continent, financed mainly by government loans. Annual credit obligations peaked at $28.4 billion in 2016, according to Boston University’s Global China Initiative.

But many projects turned out to be unprofitable. As some governments struggled to repay the loans, China cut lending. COVID-19 then forced the country to turn inward, and Chinese construction projects in Africa fell apart.

No recovery in government loans is expected.

Policymakers in Beijing have instead pushed Chinese companies to take equity stakes and operate the infrastructure they build for foreign governments. The aim, Chinese analysts say, is to help companies win higher-value contracts and, by giving them a role in the game, ensure the projects are economically viable.

Lending to Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), perhaps the most common vehicle for PPP infrastructure investments, has grown as a share of China’s overseas lending, according to figures shared exclusively with Reuters by AidData, a research center at American University William & Mary.

The $668 million Nairobi Expressway, a public-private partnership built and operated by state-owned China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC), could be a proof of concept for the model in Africa. Since opening in August 2022, the toll road has allowed commuters to travel faster than the Kenyan capital’s notorious traffic congestion, exceeding revenue and usage targets.

Daily average usage in March was already 57,000 vehicles, exceeding the 2049 target of about 55,000 set by CRBC in a 2019 presentation on the project’s economic viability, seen by Reuters.

But few companies are following CRBC’s example in Africa. While globally between 2018 and 2021, the most recent year for which AidData figures are available, around 45% of Chinese non-urgent loans were to SPVs, for Africa this figure was just 27%.

Analysts point to a number of likely reasons, including a lack of legal frameworks for PPPs in many African countries and the view of some Chinese companies (many of them relative newcomers to PPPs) that African markets are risky.

China’s Foreign Ministry did not directly respond to a request for comment on the lower SPV figures for Africa. But it says the government is encouraging Chinese companies to “actively develop new forms of cooperation,” such as PPPs, to bring more private investment to Africa.

GROWING INVOLVEMENT

The Griffith Asia Institute estimated China’s total involvement in Africa – a combination of construction contracts and investment commitments – at $21.7 billion last year, making China the largest regional recipient.

Data from the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington-based think tank, shows investment will reach nearly $11 billion by 2023, the highest level since it began tracking Chinese economic activity in Africa in 2005.

About $7.8 billion of that went to mining, such as the Khoemacau mine in Botswana, which China’s MMG Ltd bought for $1.9 billion, and cobalt and lithium mines in countries such as Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The hunt for crucial minerals also stimulates the construction of infrastructure. In January, for example, Chinese companies committed up to $7 billion in infrastructure investments as part of a review of their copper and cobalt joint venture agreement with the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Western and Gulf powers are also racing to take the lead in the world’s energy transition, with the governments of the United States and Europe backing the Lobito Corridor, a rail link to bring metals from Zambia and Congo to Africa’s Atlantic coast.

However, African leaders are struggling to secure funding for some other priority projects.

Despite the success of the Nairobi Expressway, for example, work on several Kenyan roads stalled when the government ran out of money to pay Chinese construction companies.

During a visit to Beijing last October, President William Ruto requested a $1 billion loan to complete the projects.

A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman, Wang Wenbin, said discussions on the request were ongoing. Kenya’s finance ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

The final phase of a railway line to cross Kenya from its main port to the border with Uganda has been in a similar situation since Chinese funding dried up in 2019. Uganda canceled the contract for its part of the line in 2022 after Chinese backers withdrew. out.

Asked about the drop in lending for African infrastructure, Chinese officials point to a tipping point in trade and investment, arguing that BRI-generated trade is boosting Africa’s prosperity and development.

Two-way trade reached a record $282 billion last year, according to Chinese customs data. But at the same time, the value of African exports to China fell by 7%, mainly due to a drop in oil prices, and the trade deficit widened by 46%.

Chinese officials have tried to allay the concerns of some African leaders.

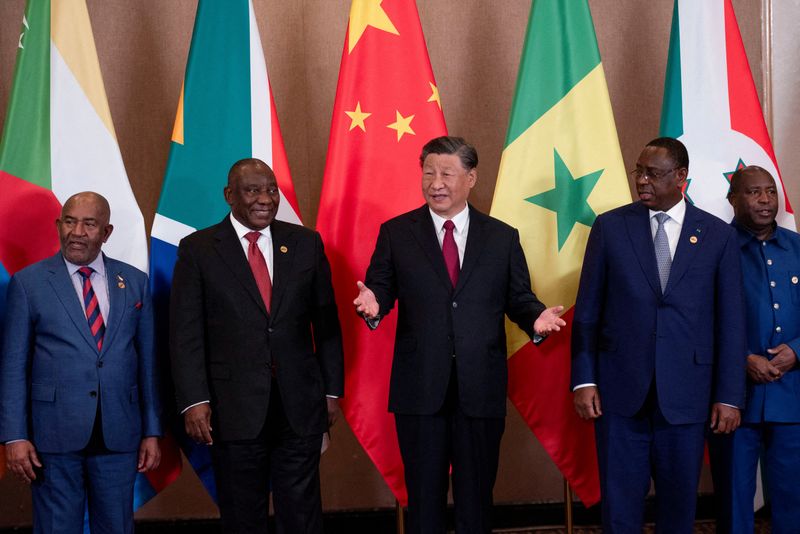

At a summit in Johannesburg last August, Xi said Beijing would launch initiatives to support the modernization of the continent’s manufacturing and agricultural sectors – sectors that African policymakers consider crucial for closing trade gaps, diversifying their economies and creating jobs.

China has also pledged to increase imports of agricultural products from Africa.

Such efforts have fallen short for the time being.

With one of Africa’s largest trade deficits to China, Kenya has sought to increase access to the world’s second-largest consumer market, recently gaining access to avocados and seafood. But cumbersome health and hygiene regulations keep Chinese consumers out of reach for many manufacturers.

“The Chinese market is new,” says Ernest Muthomi, CEO of the Avocado Society of Kenya. “It was a challenge because you have to install the equipment for fumigation.”

Of the 20 billion shillings ($150.94 million) worth of avocados exported last year, only 10% went to China.

Overall, Kenyan exports to China fell by more than 15% to $228 million, Chinese customs data showed, as a drop in titanium production led to a drop in shipments of the metal – a key export to China.

But Chinese factory goods kept coming.

That is not sustainable, says Francis Mangeni, advisor at the Secretariat of the African Continental Free Trade Area.

Unless African countries can add value to their exports through more processing and manufacturing, he said, “we are just exporting raw minerals to feed their economies.”

($1 = 132.5000 Kenyan shillings)